Artist and writer

DELANEY MAITLAND

By Delaney maitland:

“Harvest Valley”, Tobeco Journal, 2023. Print Only.

The thing I remember most is the air: the crisp, cool feeling inside the cement-floored building; the echo and reverb when you called from one room to the next; the fresh taste of greenery despite the musty smell that accompanied the space. Spider webs, full and heavy with dust, swayed in the slight breeze. If the wind was blowing just right, it would whistle through the cracks in the red wooden door, rocking it until it rattled.

I remember the rest in pieces, fractured by seasons and birthdays and summers, come and gone. The farmer’s wife, who would always ask me what I was eating that day: granola bars, off-brand Cheez-Its (a taste I’ve outgrown), and apples that I devoured like candy. The feeling of those apples—the way crunched and split in my mouth, the way their coldness made my teeth ache—takes me instantly to fall.

Every October, a corn maze magically sprung from the ground filled with creatures from my nightmares: ghosts and skeletons, zombies and witches. The farmer had a daughter my age, Carly, and we’d plunge into the depths of the maze, giggling like maniacs. Secretly, I was terrified of the thing, of leaving the shadow at my mother’s side, but Carly’s hand guided me through, pulling me deeper into the towering corn until we finally found the exit.

The victories in the corn maze emboldened us and the autumn days became ours: the farm, a great frontier for exploration. Together Carly and I ventured further to the pumpkin fields, greenhouses, and even the hay loft, which was dark and filled with scratchy towers that we climbed on like a jungle gym. Some of my earliest memories are there, in the fine ground dirt of the barn floor, though I was nearly double digits by the time I questioned why.

September 6th, 2006: I asked my mom to make a snack so I could celebrate my birthday in class. She learned the recipe from somewhere she’s never told me; perhaps a cookbook or some daytime television she watched when I was still nursing. The recipe was simple and required only Jell-O, pretzel rods, strawberries, and some grapes. When arranged with care, the food made a multicolored flower that filled me with giddy joy.

The problem with this recipe was that my mother needed grapes, and my father used our only car to get to work. But she knew of a farmer’s market only a few miles down the road; easily within walking distance.

“Can I buy some grapes?” My mom asked when she arrived at flakey painted counter of the farm stand.

“Grapes?” The cashier asked, my mother always tells me that her voice was incredulous. “Grapes aren’t in season right now. We don’t even grow them when they are.”

So, she asked for the next best thing: a job.

She’d soon learn all that grew and didn’t grow there, the seasons in which produce was ripe. She’d learn of a secret world that had always been around us: tomato vines covered in dust that made our throats itch and little wads of poison that kept slugs off monstrous heads of lettuce. Years later, she still tells the story and each time she makes the same remark, “I knew nothing back then.”

While she learned the language of agriculture, I was introduced to the language of life. I did my big books of math and reading on empty milkcrates and learned colors from bins of rainbow squash. I scraped my knees on concrete and counted the farm animals in their pens. I even lent a hand from time to time, filling crates with vegetables for the market. The farm became my second home or, more accurately, my second school. I’d get off the bus from kindergarten and emerge in a world of learning.

When winter came, the farmers had no work for my mom—the crops withered in the cold. The bus stopped dropping me at the long gravelly driveway, and instead, it dropped me at home. I didn’t miss the farm, at least not that I remember. Like most kids, I loved being at home: an oasis of toys, television, and snacks. With Christmas just around the corner, dreams of pumpkins and the sweet, crisp taste of apples were replaced by Santa and snow. But, when the world thawed out, when the grass on the ground returned, my mom returned to the farm.

My memories of spring are less vivid, perhaps because of the cold chill of winter or the endless beds of spinach and asparagus, which I wrinkled my nose at. Spring was the season of growth and preparation—gone were the days of corn mazes and painting pumpkins. Instead, I watched as my mom filled seed trays with thousands of pin-sized baby plants, anxiously awaiting their leafy return. When spring grew warm and cast out its permanent gray skies for the baby blue of summer, I spent my days at home with my older brothers. It wasn’t until many years later that I spent a summer at the farm.

I began working with my mom regularly when I was 15. Our days started in the greenhouses, picking beets and carrots or onions and green tomatoes. We harvested cucumbers and pickles from their 8-foot homes, their spiny leaves clinging to our skin as we trudged through the viny jungle. We washed lettuce and beans in lightly chlorinated water, leaving a mess of bugs and bleach in the farm’s large utility sinks. My favorite job, which my mom designated to me for years, was picking herbs.

On market days, I’d hike over to the high tunnels by myself, thankful to have a minute of time alone. Parsley was a boring and tedious job. It required combing through the spindly plants and picking several dozen stems to make a satisfactory bunch. If the crop was getting low, either from high sun or the late season, I’d end up picking nearly a hundred for one scrawny bouquet. There was the occasional “exotic” herb too: ones we only picked once in a while. Such as rosemary with its sticky sophistication or lemon balm that overtook other beds of plants if we weren’t careful. I always left the best for last.

There was something holy about the beds of basil: their curved, heart-shaped leaves lifting towards the sun; the hot, lovely aroma anointing my skin in heavenly perfume. I’d roll the thick, sinewy stems in my fingers, twirling the basil clippings like a baton before placing them in beautiful arrangements of green. I’d wear the smell of basil the rest of the day.

I’ve tried many times to preserve the scent to wear as a perfume; I’ve tried hanging bundles to dry and submerging them in oil. Nothing can capture the bliss of fresh basil, and I ache for it when winter comes around.

Along with the good, there was always the bad, the horrible, the downright disgusting. Bins of rotted potatoes that smelled like dead animals because we’d overgrown the crop in a wet year. If you weren’t careful when handling them, your hand would plunge into liquid decay. My brother, Ryan, couldn’t eat potatoes for years after that; they were prone to making him gag.

Garlic harvest was somehow worse than rotten potatoes and always happened on the hottest day of the year. We would go along the plastic-covered rows of dirt—the stalks of garlic rising out of the ground as high as our hips, they looked like giants tufts of grass—tying the green twine around the bunches. Then, it would take two of us to pull the bunches out of the ground and 50 or so hulls of garlic popped out at once, covered in hard, pungent earth. We’d take turns kicking the dirt off and carrying the heavy bundles to the quad parked at the end of the field, our backs aching after hours under the beating sun. The stalks were then hung to dry in a pole barn, to be used all year long. One summer a coworker and I took on the whole field by ourselves. Unlike the basil, the smell clung to me for weeks. It was easy to hate working there when the sun was high, and the temperature was well over 90 degrees. Or when the sky refused to rain, withering our crops to nothing, cracking the earth into tiny canyons.

One late-September weekend, after I’d stopped working to return to school, my mom asked me if I could help out around the farm. I agreed, low on cash as most high school students are. That weekend, I helped construct the corn maze by tying dried stalks of corn to stakes pounded into the ground. That was the first time I saw them construct the maze. There was no magic behind it, and the stalks looked short and scrawny the longer I stood there, tying them together.

I remembered the fear, the joy, I’d get from the maze as a child. The cheap plastic Halloween decorations that head seemed so real to me. Right in front of my eyes, that magic faded. And yet, I’m called back to the farm, time and time again. I no longer work there, but my mom and brother do, so I return often. Something inside of me is still stuck there, frozen in time. The 5-year-old who believes in magic, who knows nothing of the world, still lives in places, tucked behind barn doors, or swirled in with the years of dust and dirt, calling me back once more.

“Party Bathroom”, The Magazine, 2024.

In the unfinished basement of my childhood home, nestled somewhere between my parents’ overstated ambition and their unwavering college-party-sawdust-floor spirit, is a bathroom.

about Delaney maitland:

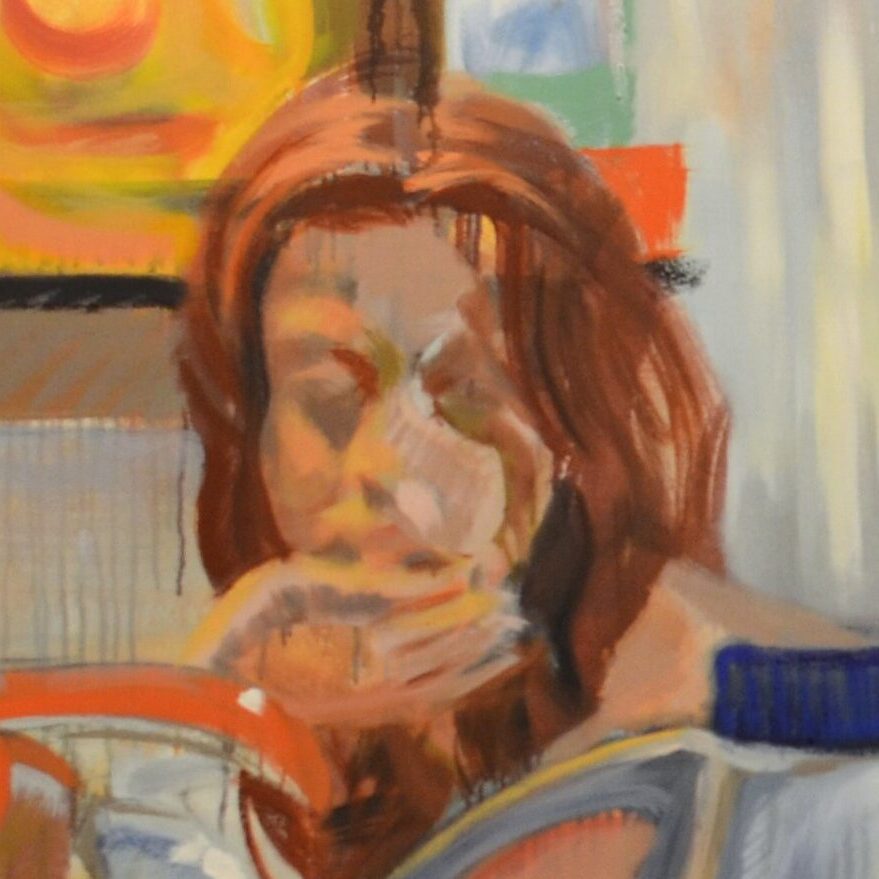

Artist Highlight in Up the Staircase Quartlerly

Delaney Maitland is a painter and writer from Mars, Pennsylvania. Though her paintings are representational, she strives to create a surface that becomes the primary focus, allowing the eyes to slowly unwind the scene. Her art has been featured in the Erie Art Museum and the Bates Gallery of Edinboro.

“ALLA PRIMA is Best Women’s Film” by Brian Fuller

In a hub of South India’s rich Tamil cinema, a PennWest student documentary is earning deserved recognition for women in arts…